I read the newspapers very rarely. I always more or less hated this, perhaps in response to this period of my childhood when, during the rainy vacation days spent in my native Morvan, my only resource to fight against boredom was reading the Superman strips taken by the newspaper La Montagne ...

More generally, I always vaguely challenged this view the news through the small end of the telescope, which is more interested in the boules competition Petaouchnouk friendly-sur-Sevre that the conflict in Darfur, and these newspapers in which the major interest of many readers is to consult obituaries if his neighbor will be included.

[I am a little moody, probably disrupted by the switch to winter time]

However, there are few, having at my disposal one of the bibles of Breton medium (outside The Holy Bible of course), namely the newspaper Ouest France, I came across this little story present in the edition of 27 October I am going to narrate.

Once upon a time, in a small town of Ille-et-Vilaine, a nice head of station, named Eric. This was exposed, like all his fellows, the recurrent difficulties of fuel supply due to deposits blocked by hundreds of trade unionists - a dozen police said, opposed the pension reform.

Being of a generous nature, he said it would be desirable to inform all those poor motorists wandering like lost souls in search of the Grail container, not the blood of Christ, but good and heavy diesel. He then had the idea to inform them in real time (?) Via the Facebook page of the large area which holds the gas station. Alas, far from stopping there, noting that competitors' prices soar during this period of shortage, the margins from his post of about 1% to 6% for certain, he courageously decides to lower fuel prices it provides and, icing on the cake, to increase its capacity by hiring extras to limit the length of queues.

Result? dozens of messages of encouragement and appreciation for this welcome improvement and these generous prizes on the Facebook page of the supermarket. Eric, moved to tears (well, there I am a bit of a film) decides to organize a challenge : If before 8 am Tuesday, October 26, one hundred were clicked "love" on the popular Facebook page, the price of fuel down. But Eric goes further, if in addition to that, 800 Internet users say they are fans of the aforementioned page, diesel oil is sold at cost. Apotheosis: If the page has over 1000 fans, all fuels are at cost.

In fact, at the end of the period, 109 people said they "liked" it, and suddenly Eric, overwhelmed by an emotion that one can not declare legitimate decided to provide all fuel cost all day going far beyond its initial commitment. Therefore predictable supply disruption from 17.45 on the same day!

player, do you doubt that what I'm interested in here is to give a little economic sense in this paradox: a manager who agrees to sell at cost upon the fact that anonymous users have served him in sufficient numbers they were nice! Notes that many users may have said the friendly, it does not cost much and moreover, they may actually find it really unpleasant, but that's all that matters, is that ultimately, a sufficient number of people have reported finding its sympathetic action.

What I mean by that is that the power of retaliation by the Internet in case of non compliance with the floor manager is relatively limited. These are not 100 Internet, which, moreover, are not necessarily regular customers of the resort, which will be able to punish the manager by boycotting their station for example. Furthermore, one might think that an objective of building a reputation by the manager to its clients is probably real, but not necessarily the main motivation for his behavior.

The question is whether this type of reward ("I" on Facebook) or punishment ("I do not like") has a symbolic effect on the behavior of individuals. This idea is as old as the world or almost one of those who argued so serious as for example the sociologist Emile Durkheim.

These penalties / rewards are said to be immaterial (also known as positive or negative feedback in the experimental literature) in the sense that they do not affect the material welfare of the officer punished or rewarded, but only his emotional state. The examples are numerous, both possible expressions of approval and disapproval verbally and facially are many insults, social ostracism (see the sweet process of excommunication), humiliation (etc.) but also the applause the encouragement, smiles and other expressions of individual or collective enthusiasm with regard to the conduct of a person.

Initially I thought count by tens experimental studies devoted to this simple question, and it is clear that it is not so easy to find items which directly address this issue in the field of experimental economics or behavioral economics in this precise sense. Many studies exist on the impact of sanctions / reward material, also on the question of the impact of sanctions on symbolic contributions (including a paper known to one of my colleagues and co-authors, David and Masclet in Masclet al., 2003). However, feedback suggested - some level of disapproval of such non-material is always ex post, once the actual decisions of individuals made public for the whole group.

The only study to my knowledge on this subject is that of Perez-Lopez & deliberateness in 2010 in the Journal of Economic Psychology , the question raised by these authors is precisely my opinion the main outcome of the enigma of my sympathetic manager behavior gas station. How the presence of an approval or disapproval of a non-material can influence the choices?

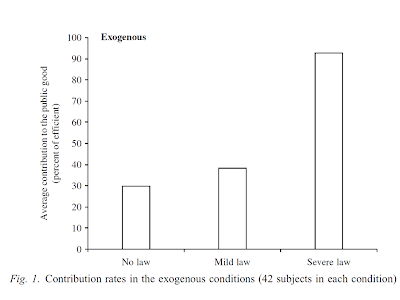

To study this, the authors, after building a model of aversion to the disapprobation, compared three treatments based on a prisoner's dilemma game played once (one-shot game ") in order to test the theoretical model constructed initially. In this game , need I remind invented by Dresher and Flood in 1950, and contextualized by Tucker in 1952, two players must decide to cooperate or not cooperate (these terms are not used in the game instructions) The choice is simultaneous. If both cooperate, they each earn 180 points, and if both do not cooperate, they each earn 100 points. If one of them cooperates and the other not, one who earns 80 cooperates and who does not cooperate earns 260 points. The Nash equilibrium is obviously a mutual defection.

The first experimental treatment is a control treatment, participants are paired with two randomly and anonymously play the prisoner's dilemma. In the second treatment, made in particular to test their model aversion to disapprove, the subject must say this before choosing their strategy, what they think their opponent will think of their choice in all possible configurations of game, if they turn clear or approve each possible strategy. For example, assuming that the other cooperates, the fact that I cooperate myself should be overwhelmingly approved by my partner. This information will be the opponent, each player having access to this hypothetical judgment actions of the other by himself.

In the last treatment, players have the opportunity, once made their decision to send a message to their partner expensive ("Feedback"), this message saying that the choice made by the other was either good or bad or neither good nor bad. The treatment that interests me most is obviously the second treatment, based on the hope of being approved or disapproved by the partner.

The results are summarized briefly: the rate cooperation is higher in the treatment feedback (which is in line with the existing experimental studies on the impact of sanctions on non-material cooperation) than in the control treatment. Treatment "expectations" - expectations about what my opponent will think of my action - is intermediate, that is to say that the cooperation rate is slightly better than in the control treatment, although the difference is not statistically significant (on the graph below, the rate of participants who chose "cooperate" in terms of treatment, control treatment blue, orange treatment "expectations" and feedback processing in yellow).

Source: Lopez-Perez and deliberateness, 2010

Thus, only certain players are showers in disapproval, but clearly this is not the overwhelming majority of participants.

Finally, drivers of large area have been lucky to come across a manager who, fundamentally, is certainly not altruistic, but rather sensitive with respect to the other, motivated by a gesture approval of his peers, which admittedly is the case for many of us.